So, today will be all about how I initially approach schools and make bookings, and my next post will be devoted to what actually happens on the day of the school visit itself.

First of all, a writer who wants to go into schools ideally has to write for children or teenagers. And then, you have to go about promoting yourself - and that's the hard bit. It's very important to say that this stage that it's part of our work, and as most writers are freelance artists we should be up-front about charging a fee. This will vary from writer to writer. Some people think writers should earn only from their books and should do school visits as 'publicity' or out of the goodness of their hearts - I could not disagree more with this, and I know from conversations with fellow children's novelists that almost everyone agrees with the principle of charging the school a fee for the day. Most of us could not live from our writing alone, and most published writers have, as I do, a 'portfolio' of work which includes writing, editing, mentoring, festival appearances, school and college work, teaching of adults, etc. However, charging the parents a one-off fee so that the school can afford the day is something I'm more uncomfortable with - the school should really only invite a writer in if they have the funding. (A special evening event or talk is a slightly different matter, and schools often fund these by asking parents for a contribution or a small ticket price.) Some very high-profile writers - literally a handful - can afford not to charge a fee, and so I believe they should ask it anyway and donate the fee to a charity.

|

| Real Live Author about to be deleted by the Cyberleader, aka Mr Drury at Ecclesfield Primary School. |

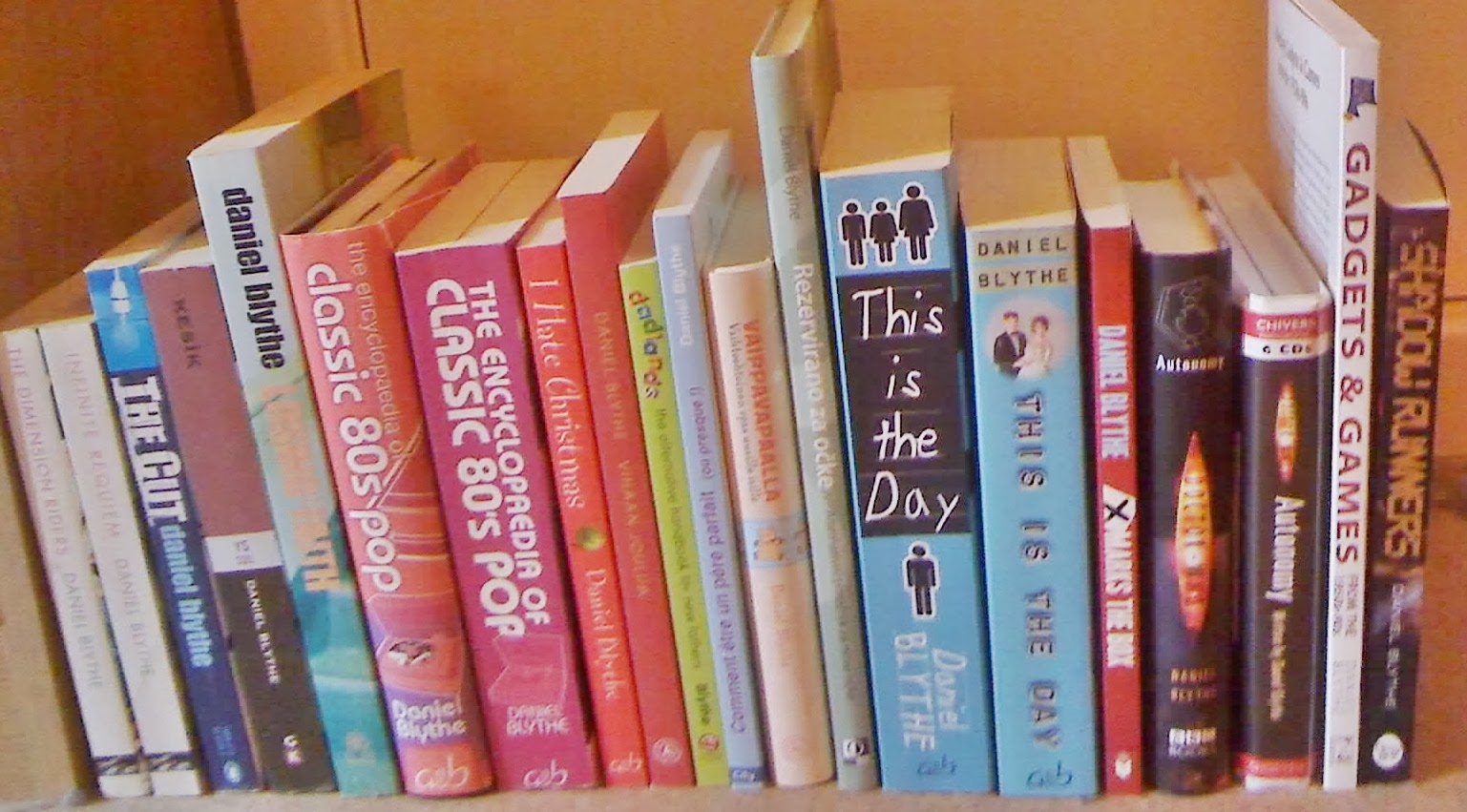

Initially, back in 2007-09, my talks and workshops were very general and didn't really refer much to my own work. It helped a lot when my Doctor Who novel Autonomy came out and that I'd put together a Who-based presentation about the history of the show - initially just with slides and sound, and later with video clips too (which can come fraught with its own problems). I've only done a small amount of Who work compared to some people, but it has paid huge dividends in terms of publicity and visit-booking - most children are enormously excited to meet anyone even slightly associated with the programme. I imagine that if David Tennant or Matt Smith walked through the door, some of them would probably faint. Of course, you get the odd one who knows nothing about Doctor Who - I always tell them they'll learn the most today - or the glum-faced one who says they hate it, and I react in horror and ask them why on earth they were watching Ant and Dec's Celebrity Dwarf-Tossing on ITV. (Yes, my good friend and colleague Lord Keith Telly of Topping used that joke too, but I seem to recall I gave him the line once, long ago...) But I even win some of those over in the end.

Shadow Runners arriving in 2012 helped enormously too - this book, published by Chicken House, is aimed at readers aged 10+, and so (being a bit creative with that age-banding) I can say that good readers in Years 5 and 6 will enjoy it, as well as those of secondary school age (Year 7 and above). Most of my school talks and workshops these days are aimed at Years 5 and 6 in primary schools, or years 7 and 8 in secondary schools.

I'm on a couple of writer databases - Contact An Author and Start The Story. They've got me bits of work in various schools. I'm also registered with Authors Aloud, who have only been up and running a short while but have already got me two school bookings and a morning at the Wessex Children's Book Festival in Winchester earlier this autumn. Some people no doubt find me through my own website as well, which has details about school visits on plus testimonials from happy schools!

Word of mouth is effective too. I've met some great librarians and teachers who have done their bit promoting me in various parts of the country. In contrast to other businesses, there is limited potential for 'repeat work' - a school won't necessarily have you back, even if they've liked you, because they'll be keen to try another author for the sake of variety. Nevertheless, I've done repeat performances at several schools over the last few years. Various friends have done their bit too, bigging me up in their local schools in Essex, Oxfordshire and Geordieland.

And then there's the unsolicited approaches. This part of the job makes me feel a bit like a door-to-door salesman hawking my wares, but it has to be done - and out of every 100 or so emails, one or two responses lead to a positive outcome. Some have suggested to me that a 1-2% return on 'junk mail' is an amazing response and that I should be delighted with it, but it does make me wonder what on earth happens to all the others. I imagine they just get plonked into a school secretary or headteacher's spam tray. In three years of taking this approach, I've only ever got two terse 'Unsubscribe' responses, and one from a head teacher who obviously hadn't had his coffee (or maybe his pills) that morning and whose reply screamed 'DO NOT EMAIL ME!!!!!' down the wi-fi at me, almost knocking me out of my chair. Also, what I send isn't 'junk mail' - I take great care not to 'spam' schools with BCC messages, but rather send each one an individual email addressed to the head and the school by name. Sometimes I'll refer to something nice and writing-related on their website, if I can find anything. I've made approaches by post, too, mailing out my writer information packs to librarians, but sadly I think I will stop doing this in future, as it is quite a costly way of going about things and, as yet, hasn't resulted in enough bookings to make it worthwhile...

And then there's the unsolicited approaches. This part of the job makes me feel a bit like a door-to-door salesman hawking my wares, but it has to be done - and out of every 100 or so emails, one or two responses lead to a positive outcome. Some have suggested to me that a 1-2% return on 'junk mail' is an amazing response and that I should be delighted with it, but it does make me wonder what on earth happens to all the others. I imagine they just get plonked into a school secretary or headteacher's spam tray. In three years of taking this approach, I've only ever got two terse 'Unsubscribe' responses, and one from a head teacher who obviously hadn't had his coffee (or maybe his pills) that morning and whose reply screamed 'DO NOT EMAIL ME!!!!!' down the wi-fi at me, almost knocking me out of my chair. Also, what I send isn't 'junk mail' - I take great care not to 'spam' schools with BCC messages, but rather send each one an individual email addressed to the head and the school by name. Sometimes I'll refer to something nice and writing-related on their website, if I can find anything. I've made approaches by post, too, mailing out my writer information packs to librarians, but sadly I think I will stop doing this in future, as it is quite a costly way of going about things and, as yet, hasn't resulted in enough bookings to make it worthwhile...A successful booking usually starts with either the relevant teacher or librarian asking me what I can do for them, or coming to me with an outline of what they like. On balance, it's easier for me when the librarian does it, because their focus will be on promoting reading for pleasure and not on the dreadfully rigorous government-imposed 'levels' of the literacy framework which teachers are, against their better nature, forced to work within. Nothing makes my heart sink more than a school which expects a writer to come in and sprinkle 'magic writer dust' to get their 'difficult boys' up from Level Splurg to Level Fnarg (I should know the actual names of these, but frankly I don't care what they are and neither should you). I have to bite my tongue when I want o say, 'Look, if you haven't managed it in two terms, there's not a lot I can do in six hours!' And sometimes, things can go horribly wrong when you decide to pin all your writing to the mast of 'Literacy'...

|

| Oops-a-daisy. |

We agree a date and which year group(s) I will be working with. I'm happiest with Years 5, 6, 7 and 8 (that's ages 9 to 13, in case, like me, you went to school a while ago). But I will work with the younger Juniors, and I've got a couple of workshops which can go well with the older teenagers. I do politely but firmly decline offers to lead workshops with the Key Stage 1 classes (infant school, in old money) - not because I don't like them, but because they are too young for any of my books and I don't have anything that works with them. There are lots of lovely authors out there writing for 4-to-7-year-olds who know far more about engaging that age group than I would, and I'm happy to leave those days to them!

We hammer out the details of what they want and what I can provide - and what I'll need in terms of resources. I actually need very little for most workshops, because I come along armed with folders full of exercises and photos to inspire writing. All the children need is a pen or pencil and a piece of paper or a book to write in. (The first few times I went into schools, it was quite an eye-opener what a fuss and commotion it could cause just getting those ready! Never assume they'll just be carrying pencils around as a matter of course...) My talks require a bit of technical support as I run everything off my own laptop and I need to plug it into a big smart-board or a projector, whatever is available. The use of video means I never take any chances using someone else's laptop these days, as it invariably means that those particular Powerpoint slides will end up looking like useless black monoliths from the Dawn of Time. I also ask for speaker sound to be available, which is simplicity itself for some schools and a bit of a headache for others. If it really isn't possible, then I have my portable device which I call The Little Muffin, a good investment from last year and a device which I was first introduced to by the lovely people at Frome Library!

We agree if books will be sold at the event, and if I am providing these (and ideally how many, as I'll be coming on the train and I need to know if I can carry them). Some schools will sort sale-or-return copies from a distributor, or will get a local bookshop to come in and run a stall. Then I sort out my travel and other details, and I have a standard letter which I ask to go out to parents so that they know their children will need money if they want to buy a book. I send that, plus my invoice, in a final rounding-it-all-up email about three weeks before the visit date. I always give my mobile number too, in case the school is closed through snow, alien attack or an outbreak of the Black Death the day before - that's the last thing you want to find out after you've done a 3-hour cross-country train trek. I'm proud to say that in 5 years and over 250 schools, I've only once been a bit late (which was thanks to a Manchester train being delayed by 40 minutes in a landslip, and even then I wasn't late starting the actual talk), and have only once had to cancel, when I was so horrifically ill that I could barely lift myself off the bed to reach the phone. I'm done a few schools when I've felt a bit under-the-weather - croaks, snuffles, headaches and the like will not stop me!

So, next time round, I'll talk about what I get up to on my visits - and I'll be sharing tales of 11-year-old Doctors, Weeping Angel Teaching Assistants, papier-mâché Daleks and so on, plus creatures that hide in chimneys and The Capital Letter Story. And there will be visual evidence of the Lincolnshire library which actually let me graffiti its wall... Plus I may have one or two horror stories to share - and I don't just mean things that go bump in the night...