Do you know what the ten things never to say to a writer are? If you don't, here's Chuck Wendig to brief you. A lot of that resonates with me. I wrote an article for The Author a few years ago about the ten most annoying questions writers get, and it touched on a lot of similar ground (and resulted in a very nice handwritten reply from J.K. Rowling!).

Like most other writers, I probably get asked the one about where ideas 'come from' more often than anything else, and I give a similar answer to Chuck's - you just can't stop them coming. I currently have 63 'blurbs', or attempts at blurbs, on my computer. Each of these represents a potential new novel. Maybe 10 of them are actually good enough to be made into novels at some point. It's my continual fear that I won't live long enough to write all the books I have 'ideas' for.

Ideas are not the problem - it's what you do with them.

And yes, I always write a blurb because it forces you to think:

Who is this story about?

What situation are they in at the beginning?

What happens to change that?

What questions does this make us ask?

Those are the questions I use for children's workshops about story outlines too.

This is also why I am extremely sceptical when readers write scathing reviews which say 'I could have done better than that', or 'I could have written a much better novel/script about the same idea'. I may have become hard-hearted after 20 years as a published writer, but I'm afraid my first reaction is, 'no, you probably couldn't.' They think they can just pop through a magic fireplace to, say, BBC Media Centre, slap a script down on the desk and say 'read this'. It's the same mentality which draws people into being amateur football managers, and declaring - usually every 4 years after England is knocked out of a major competition in the early stages - 'My Sunday league team could have put up a better showing against Costa Rica/Portugal/ Italy/delete as applicable.' Our national team is not the force it once was and is, sadly, distinctly average on the world stage, but even so, the idea that amateurs could make a better fist of it is, come on, a little far-fetched. Yes, even with England.

Doctor Who fans are more guilty of this than anyone. There is a tendency - especially since the show came back, first under Russell T Davies and then under Steven Moffat - for fans to fulminate that they could be writing scripts which are better than what has ended up on screen, and indeed in some cases that they could even be running the show more efficiently.

What is rather telling is that they always choose the worst example of Who they can find, and say things like 'I could wee Fear Her in my sleep', or 'I've had dreams that have been better-plotted than The Rings of Akhaten'. I make no comment as to the merits of those stories - they are the favourite of someone, somewhere, as the Doctor Who Magazine 50th Anniversary Poll reminded us - but just observe that they're generally rated lower than their bedfellows. So why set your sights so low? Surely any aspiring TV writer should choose the best example of Who (or Buffy, or Casualty, or Midsomer Murders, or whatever their bag is) and say, 'One day, I want to write a story as good as Pyramids of Mars/The Caves of Androzani/ Blink/Asylum of the Daleks'?

This excellent piece by Lee Zachariah says everything I want to say about the reasons the current incarnation of the show upsets a certain kind of fan a bit too often. A dimension which Lee doesn't mention so much in his - perfectly valid - comparisons with other programmes is the sense of ownership which Who fans feel over the show, one which really came into its own during the two big gaps when Who was off the air (sob!) in the early 90s and late 90s/early 00s. That was the point at which fandom took over the controlling narrative, and after which any 'official' version of the programme was going to have to compete with the fan text rather than automatically trumping it. It's very different from the way fans interact with, say, JJ Abrams, Josh Whedon and J Michael Straczynski about their shows. Yes, some fans are annoyed by Steven Moffat for a very simple reason - he isn't making the version of the show which exists in their head. And so his ideas must automatically be inferior to theirs - even though he is the one with 25 years' experience of writing for TV.

Some people take it even further and argue for a return to the halcyon days of the New Adventures' open door policy (from which I and others did benefit). They say the BBC should no longer insist that people writing for Who come from established TV backgrounds, and that it should open script submissions up to the general public.

I'll tell you what I think about this.

I think that is the most ridiculous idea I've ever heard, and is a recipe for disaster.

Let's imagine for a second a lunatic parallel universe in which this actually happens. None of these script submissions would even be seen by Steven Moffat. They would be sifted through by some lowly BBC employee who would, slowly, lose the will to live as he/she reads the hundredth barely-literate, action-packed effects-fest in which multiple incarnations of the Valeyard take on the Daleks as they battle the Ice Warriors for control of Mars, or in which the Rani teams up with Sabalom Glitz on Peladon. Even those which were not continuity-laden, unfilmable nightmares would need bashing into shape through about seventeen different drafts before they produced anything remotely resembling a TV script. And it's likely that the best idea - the best story - which could slot into a new season of Who would come from someone who had ten years' experience of writing scripts for TV anyway, thus invalidating the entire process. Opening up Doctor Who script submissions to Joe Public would be to deny that Who is in fact a very difficult programme to write for. It would be like turning auditions for the London Symphony Orchestra into The X-Factor and allowing people to have a a shot when they haven't even done Grade 1 violin.

All right, it's the way publishing still works - most of the houses allow submissions (although increasingly they have to come through an agent), even those with no previous novel experience. Genius novels are found on the 'slush pile'. But TV is a very different beast, and even competent writers with lots of experience in other media, e.g. books or audios (I feel able to count myself among that number) do not necessarily have enough of a grasp of the basics of TV scriptwriting to produce a workable new Who. (When I do talks, I find myself comparing different kinds of writing to different kinds of running - it's rare, almost impossible, to excel in both sprinting and distance running, for example, as your training is totally different.)

And the people who say 'I could do better' think they can simply send their 'finished' (i.e. probably utterly unworkable) Who script off to the production office, rather than going through the more realistic, more tedious process of building a reputation: getting stuff published in small magazines, building up a CV through short films and soaps, having a script 'calling card', going through processes like BBC Writers' Room, script workshops and networking and so on. There's no one way to do it, but the ways in which people do it usually cover two or three of those bases.

It can take ten years or more of that kind of thing before you're ready to tackle a 50-minute episode of a highly-regarded show. But some people don't want that. They want their genius to be discovered now.

When I was first published, I knew nobody in publishing and knew nothing about it. The people I now know, and the knowledge I have picked up, is the result of 20 years' experience. I am a much better writer now than I used to be, because I have listened to people, and I have read more, and watched more, and thought more. That was never going to happen overnight. And I'm not published because I 'know' (actually not very well) some people in publishing. It's the other way round.

So, if you're angry enough to be watching a professional at work and think, 'I could do better', then by all means have a go. Anger is an energy, as a prophet said once. But I'm afraid, it's a case of - depending on what you want to get into - practising your scales, learning your dribbling and passing skills, or writing for non-paying, non-glamorous markets for a bit.

And there's no magic fireplace to let you jump through time to the required spot. You've just got to clink glasses with Madame de Pompadour and celebrate doing it on the 'slow path'.

Good luck. It's what the rest of us had to do.

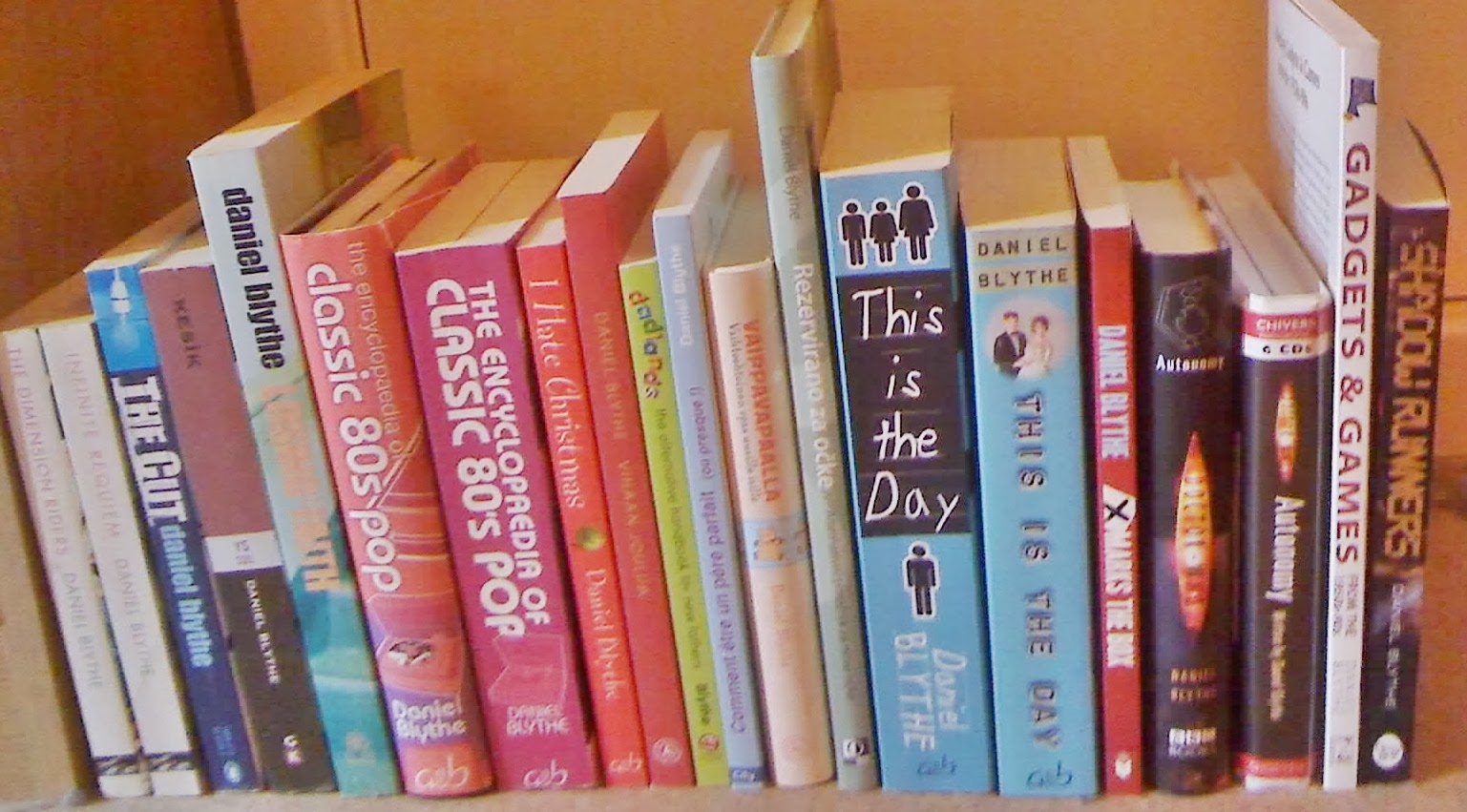

The occasional blog of writer Daniel Blythe (Doctor Who, Shadow Runners, 80s Pop, The Cut and other stuff).

The Books

Tuesday 16 September 2014

Friday 5 September 2014

The One About A TV Show That Is Not Doctor Who

At the risk of sounding like someone who writes in to the local newspaper to rant about whatever is on their mind, you know that song, 'it's 5 o'clock somewhere?' Well, it's always the 20th anniversary of something somewhere, these days. These anniversaries sneak up on unwary 45-year-olds who are still getting accustomed to not being 30: the first Iraq war, Britpop, Nirvana's Nevermind, Tony Blair becoming Labour leader, Jarvis Cocker showing his bottom to Michael Jackson at the BRIT Awards... (Wait, we haven't had that one yet, have we? That's next year. I hope.)

The early series of Friends actually have a haunting, nostalgic, almost elegiac quality in places. There is the sense of regret beneath the comedy that these people will never get their childhood and high school years back, and the freedom and fear of being unleashed into the adult world - especially when viewed on the rather washed-out, grainy prints E4 seemed to use. (Or did it always look like that?) Later series sometimes descended into farce, and it was tricky to ignore the fact that the regulars increasingly looked like highly-paid, airbrushed supermodels, but it was usually very funny. It's not hard to see why it did so well here in the UK, as it has all the staples of a great British sitcom: a small group of characters (which doesn't change at all in 10 years - even Dad's Army and It Ain't Half Hot Mum lost a couple of regulars) and comedy which is often based around misunderstandings, social embarrassment, irony, characters behaving in predictable ways, and people trying and failing to pass on important messages until it's too late.

It's interesting to think about the few things which a UK version might have made more of, but which are more-or-less ignored. The Geller family's Jewishness is just there, it's hardly ever really made a big thing of (which is fine), and yet it's hard to imagine a UK sitcom with a Jewish family which would not make their religion a central issue - and sadly, it would probably lapse into comic stereotype. Also almost totally glossed-over are the obvious income differences there would be between a head chef, a very-occasionally-employed actor, a singer/masseuse, a data input thingy whatsit (what does Chandler do, anyway?), a university lecturer and a waitress. (I say almost, because there are odd references to it, and one episode where it is, rather jarringly, pointed out that three of them earn less than the others.) The awkwardness would be made more of in a British sitcom - and it would probably also be a class-based issue, with the comedy arising from the ensuing social gaffes (think of Rodney and Cassandra in Only Fools and Horses).

A few elements proved odd for the British viewer, though (I'm hoping it wasn't just me) so I thought I'd round up a few of the cultural oddities which sometimes proved a barrier to enjoying the show properly. I don't mean stuff like the importance of High School proms or (mostly) issues of vocabulary, or how darned odd it sounds the first time you hear Phoebe say 'I'm a mass-oose' to rhyme with 'caboose', and not the much sexier and more Fruunnnch 'mass-euse' to rhyme with 'Chartreuse'. I'm not talking about high-fiving, belief-suspending riffs of plot ludicrousness like Rachel's meteoric rise from waitress to Ralph Lauren buyer (is nobody in US sitcoms allowed to stay unsuccessful, or be poor or have unfulfilled dreams?). Or Joey's apparent ability to work on a Los Angeles-based TV production while living in New York all the time, or the increasing unlikelihood of all six of them being together for casual breakfasts before work and cosy gatherings on the Central Perk sofa in the evenings (Monica being the only chef in the world who never works evenings, weekends or public holidays).

I'm thinking of things which probably won't have been commented on by the US viewer because they are so normal, and yet which will have made most UK viewers go 'huh'? At least, until the time we saw 'The One With The Holiday Armadillo' for the seventeenth time on E4. (Seriously, it was always 'The One With The Holiday Armadillo'.)

1. Ross is a Professor.

His students call him Professor Geller. He's only just got his PhD, he's only just left the museum and started teaching. Yes, 'Professor' means something very different in the US education system, and it jars a bit when you're used to the UK one, where being a Professor entails the responsibility for an entire department - and where you're a prodigy indeed if you manage it before you're 40, let alone 30.

2. The Hallowe'en episode.

There always has to be one. And everyone dresses up in random, weird costumes whose extravagance is in inverse proportion to the humour quotient of the script. Can they not just ignore Hallowe'en one year?

3. The Thanksgiving episode.

Equally baffling. Again, there always has to be one, and there is usually an 'amusing' incident with a turkey and a crisis over a family misunderstanding.

4. 'Doodies'.

Over and over again, in the episode where Chandler starts his new job, it is apparently hilariously funny that his colleagues pronounce 'duties' in this way. It isn't even funny the first time, seeing as we don't have the same slang term (it's a toilet reference, right?), and having it repeated throughout the episode doesn't make it any funnier.

5. Pottery Barn.

We don't have it. So the whole social significance of Phoebe's antipathy to the place (despite eventually decking out her flat in its fake-antique stuff) is rather lost on us.

6. The crying Indian.

The basis of a famous Chandler one-liner, in 'The One Where They Run Out Of Petrol' (look, I know it's not probably called that, but people call Doctor Who episodes 'the one with the maggots' and 'the one with the statues' so often that I thought I could get away with it). Chandler says that if he throws some rubbish down, a 'crying Indian' would come by and save them. It's all about this environmental awareness short from the 1970s, which most UK viewers will only have discovered since we got YouTube. They probably wouldn't say 'Indian' these days... right?

7. Whooping at celebrity cameos.

Seriously, why do audiences do this? Every time a guest or minor character walks into the room for the first time and, big deal, they happen to be played by Christina Applegate or Tom Selleck or someone (yes, they play roles, they are actors) the entire studio audience explodes with a rapturous 'WAAAAOOOGGHH--HOOO!' and a deafening round of applause. Quite apart from drowning out the character's first line of dialogue, it also breaks the fourth wall (and not in a clever way) and means that, on some level, the audience are not fully buying into the fictional universe presented.

That's it.

Well, not quite. I can't let this go. For the last time:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)