By this autumn, I will have been writing professionally for 23 years - I start counting from the first time I was paid for something I wrote, in 1992. I like to think I've picked up a few things in that time - and, to be fair, I've probably forgotten a fair few as well.

In recent years I've been concentrating on writing for younger readers. As I'm now in my mid-40s, this is of course strewn with pitfalls. But then a lot of children's and Young Adult writers have the same problem, and we get over it in a number of ways.

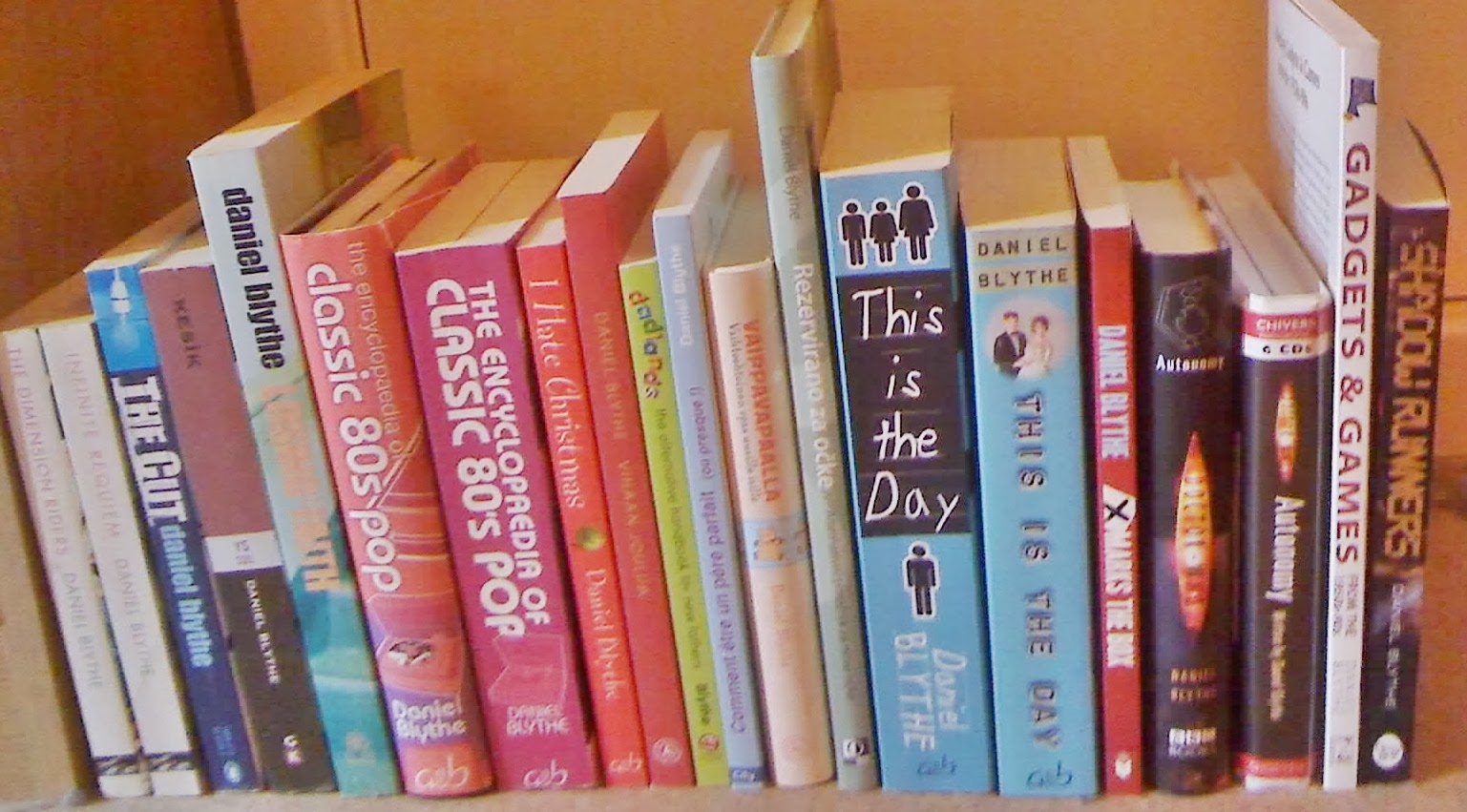

|

| Not likely to be called Maureen, Susan and Roger. Trust me on this. |

The other thing recently which has made me aware of a lot of pitfalls of writing is the work I've done - in various contexts - looking over unpublished manuscripts at various stages. As a tutor, editor and mentor I would say I've probably seen a couple of hundred unfinished books (and I include those where the writer believed them to be finished). About half of these were aimed at the teen/YA market.

Although everyone's manuscript requires individual attention, there are problems which recur all the time and which people could very easily eliminate if they knew about them. So, I've decided to present - from my experience - the

Top Ten Things People Get Wrong When Writing A Teen Novel.

1. That's Not My Name.

If the writer is of a certain age and fondly recalls the children's literature of their youth, the chances are that they will be harking back to a time when you really could have books where someone called Dick woke up stiff after a night in the barn, and someone called Julian could announce that he was feeling a little queer. You may have happy memories of a wonderful story in which Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy venture into a world beyond a wardrobe, or John, Susan (her again), Roger and Titty mess about on lakes. And while you may realise that you can't call a child 'Titty' in a novel today, you should also know that none of those other names cut the mustard any more either. (Except Lucy. You're allowed to have teenagers called Lucy. Along with other names which have survived the test of time, such as Ben, Alice, George, Emma, Oliver, etc.) So

please - no 13-year-olds called Maureen, Margaret, Alison, Steve, David, Darren... Don't choose your characters' names by mentally going through the register from when you were at school. It may seem obvious, but so many writers genuinely don't seem to realise that those names have dated. There are plenty of lists of baby names from the 90s and 00s out there, so even if you don't know any teenagers personally, there's no excuse.

2. Are We There Yet?

So many unpublished novels begin with a meandering, waffly opening chapter, usually a relic from the very earliest draft where the writer was trying to find his or her way into the voice of the book. Often, this will involve the main character arriving at a new school and getting to know a lot of new names and faces, many of whom have disappeared by the time the plot actually gets under way. You've probably only got 50,000 words or so, and you should make them count. So don't waste a chapter or two on irrelevant stuff. Your reader will be wondering when on earth you are going to get the story going.

3. A Kind of Magic.

In the last 15-20 years, novels featuring spells, magic, the supernatural, fantasy, fairies, dark demonic forces and pink sparkly custard with the ability to transform into eagles have all swept to prominence, and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that. But magic is not a plot short-cut. This is something I've seen again and again - writers bringing in a magic spell, a supernatural happening or a hitherto unsuspected ability, in order to move the story on. If you have to do that, the chances are that your book already suffers from deeper structural problems. Look at how published writers use magic. It's almost never thrown in just as a 'with one bound, they were free' way of getting the characters out of difficulty. There's a trade-off for using magic: emotionally, economically or in terms of expended force or energy. Use your magic sensibly.

|

| Hocus pocus, narrative focus. |

4. What's It All About?

In a desperate attempt to make sure there is enough going on in their novel, a new writer will often throw in everything including a magical, talking kitchen sink. Maybe you need to do this in a first draft, to work out what is effective and what isn't. But don't leave it all in. The result will not be a neatly-dovetailing denouement in which all the threads come together, intertwined with narrative genius. It will be a mess, in which all the disparate elements look as if they've wandered in from different novels. That robot clown on page 56, that Minotaur on page 98, that aquatic chariot race on page 134? They may have all seemed like a good idea at the time, and for perfectly valid reasons. But now that you've got through to the end, and you're redrafting and re-editing (you are doing that, right?), ask yourself how valid these elements are for advancing the plot or the characters. Or are they just there because you like them and can't bear to let go of them? Plonk them in a folder called Bits and Bobs. You'll find somewhere to use them, even if it takes five years.

5. As You Know, Captain...

If you have to have pages and pages of characters sitting down and explaining vast chunks of the plot to one another - as if they're either in the kind of meeting you get before a school trip, or the kind of tedious post-project debriefing session you may have had to endure at work - then you've done something wrong. This goes double if you have characters telling one another things which they already know.

6. I Quit.

There's a well-known critics' favourite called 'quitting before you're fired', and people often feel the need to include it in children's novels - perhaps fearing the young reader will be so disgusted by the scientific implausibility of what they have just read that they will fling the book aside,

unless the author gets there first. Basically, 'quitting before you're fired' is a seemingly-clever (but actually not that clever) technique where the author, having spotted something which doesn't make sense, decides to have one of the characters point this out to another in the hope that drawing attention to it will make it look deliberate. You also sometimes see this called 'lampshading' (i.e. hanging a lampshade on anything which challenges the audience's suspension of disbelief). What the author should be expending energy doing, of course, is going back to the Thing Which Does Not Make Sense and either removing it, or making it more likely, believable or comprehensible.

7. 'I say, Julian, what a jolly wheeze.'

Part of the problem with being any age older than a teenager and trying to write teenage dialogue is that, unless you have children of that age, or are a teacher or social worker or someone else who works with young people, you won't hear much of it on a day-to-day basis. So you should make it your business to go and listen to some, in any way that won't get you arrested. Go and earwig in Subway and Nando's, or on train station platforms or in bus queues. Write down anything especially witty or interesting - because, of course, you will have your Writer's Notebook with you at all times. At all costs, try to avoid going either of two ways - having your young people speak in the voices of middle-aged people, or having them speak in a kind of forced, pseudo-contemporary way, peppered with slang which will quickly date. The best children's writers are very adept at capturing the rhythms of young people's speech, without actually using expressions that pin them down to a particular year in the 21st century.

8. The Machine Stops.

If you are writing about contemporary young people between the ages of 12 and 17, then at some point you're going to have to address the fact that, at this age, the vast majority of them will be conducting a lot of their lives on social media, either using laptops or iPads or phones. In ten years, all of that will have dated too and I'll have to come back and update this blog, always assuming anyone is still blogging in 2025. But for now, have a think about the challenges this sets us as writers. It’s rare to see anyone under the age of 30 walking around without some kind of portable communications device, often multi-tasking on a number of virtual platforms while walking, talking, eating or working. And while we can’t yet teleport ourselves out of difficult situations, the existence of a cloud of data, accessible at a thumb-nudge, changes the whole way we think and act. The prevalence of technology and social media means that much of the emotional dimension of our characters’ lives could well take place in these virtual spaces. Ignore it at your peril. (All right, so you can’t allow for every eventuality - there is always the possibility that a young reader in 2035 will download a book from the SchoolLibrarySpace, flick through it and declare in horror that it’s ‘so 2010s – the characters are called Ryan and Jade and they use

Snapchat…’)

9. Tonight We're Going To Plot It Like It's 1989.

Following on from the above - there's a good reason the

Sarah Jane Adventures team were always having their phones impounded, because mobile technology is a surefire way of short-circuiting a plot. ('Hi, Mum? The alien kidnappers have taken us to a hangar just outside Basildon. I think it's somewhere off the A132. Can you come and get us?') The ease and speed of sending data will affect the structure of our plots. In the 1980s, if Gary wanted to blackmail his ex, Trish, with an ill-judged photograph of them

in flagrante, he would probably have had to wait a few days for it to be developed – and even then, Trish would have the chance to destroy the negatives. In 2015, if Connor wants to do the same thing to Chloe, all he needs is the evidence on his phone and, in milliseconds, it can be up there for all the world to see. Spy stories involving the recovery of files – either on paper, on CD or on memory-stick – will fall by the wayside now that data zips through the wireless networks and is backed up in the Cloud, and so writers of hi-tech thrillers will need to find new, 21st-century MacGuffins to drive their plots.

10. Teenage Kicks.

You know what teenagers are like, right, because you were one? Chances are you'll get it terribly wrong, though. So may first-time writers produce what they

think is a teen book but, because they haven't read enough of what's out there, and what they produce is, as far as tone and storyline and emotional content go, a book for age 9-12 with slightly-too-advanced vocabulary and syntax for that age group. It goes without saying that, if you want to write for teenagers, you should be reading and enjoying what's already out there - and if you are, that will make doubly sure we don't get any adolescent Rogers and Maureens listening to the latest happening sounds on their Compact Disc Players.

|

| 'What's your problem?' |

Remembering our own childhood is not good enough - yes, today's teens live through the same emotions and experiences as we did in the 1980s. But on the other hand, the context is very different. I grew up in that 12-year gap between the arrival of computers in the home and the day when some bright spark first had the nous to plug one into the telephone socket. If you travelled back in time and told me about social media, revenge porn, Instagram, people filming rock-stars' unfortunate hair-burning accidents and putting them on YouTube, vloggers getting book deals, apps, Snapchat,

Clash of Clans and the entire

raison d'être of something called a Kardashian, my head would probably have exploded. I was still having trouble with the idea that the Hobbit game could talk to me. THORIN SITS DOWN AND STARTS SINGING ABOUT GOLD. If you'll excuse me, I'm off to feel middle-aged.

Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O'Farrell

Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O'Farrell